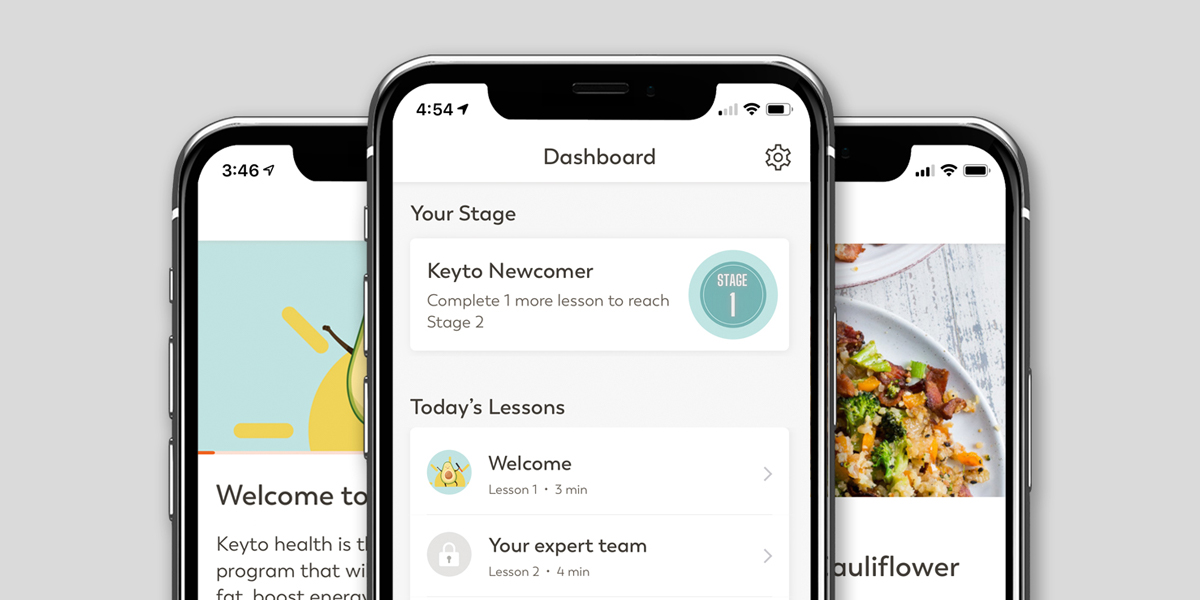

In the previous article, we outlined our process to design Keyto, which is a Mediterranean-style ketogenic program. In summary, we used the best scientific evidence to arrive at a program that achieves the metabolic benefits proven with ketogenic diets, while also optimizing for LDL cholesterol levels.

After program design, the next step was to find out if our program was actually effective. We wanted to test ourselves in a gold standard experiment, a randomized controlled trial (RCT). While this step seems obvious, virtually no consumer health companies ever do RCTs. Why?

The reason is that RCTs take significant time, effort, and money to complete. In contrast, it is much easier, faster, and cheaper to make baseless marketing claims, or do non-randomized trials which may be strongly biased and result in “better-looking” outcomes due to lack of objective randomization or a relevant comparator group.

Also, as opposed to the FDA regulatory process required with drugs, the FDA does not review low-risk health and wellness products. Thus there is no regulatory approval incentive.

So are RCTs worth it? For us, the answer was a resounding yes. Our ultimate goal is to build a company that can improve the health of millions of people. It was essential to first find out if our program actually works as designed.

For us, the term “works” meant two things.

First, if a user follows the program, will that user improve their health as measured by weight loss and/or health markers? We were particularly interested in markers for diabetes, cardiovascular risk, and liver health.

Second, can users adhere to the program? In other words, is the program doable? A program that achieves great health results is worthless if it is too difficult to follow.

The only way to answer both of these questions in an unbiased manner was to conduct an RCT. For those less familiar with trial design, RCTs have attributes that make them the “gold standard” for experiments. The most important one is that they are “randomized,” meaning that a given participant may receive any test condition. As described by Hariton et al:

“Randomization reduces bias and provides a rigorous tool to examine cause-effect relationships between an intervention and outcome. This is because the act of randomization balances participant characteristics (both observed and unobserved) between the groups allowing attribution of any differences in outcome to the study intervention. This is not possible with any other study design.”

In addition, RCTs have the endpoints of the experiment, namely what is being measured, defined before the trial starts. The trials are “prospective,” meaning participants are recruited, randomized, and given the intervention after the trial is designed. This is in contrast to retrospective studies that look back at historical results. All of these attributes reduce bias in the experiment.

With this background, it was clear for us that we had to do an RCT.

We were fortunate to find a reputable academic partner in the University of British Columbia for this project. They would be responsible for designing and conducting the trial. This planning process started in Spring of 2019.

It was first decided to compare our program with an active comparator (as opposed to a “usual diet” group). This was a bold move as it would be more of a guarantee to be shown more effective than no program at all.

UBC’s next idea was to use the DASH diet as our comparator. While the DASH diet is endorsed by the American Heart Association, it does not have a full featured app. We did not think this test would be quite fair.

UBC then suggested the active comparator be Weight Watchers (WW), the biggest name in weight loss. WW had a low-fat, low-calorie program, a full featured app, and a long history of published weight loss results. While we knew it would be a bigger challenge to show superiority vs WW, we also knew this was the right comparator.

Our trial design was published on clinicaltrials.gov in November of 2019 (link). We also published a protocol paper with more details (link).

In summary, It would be a 144 person (later revised to 155 persons due to the COVID-19 pandemic) trial with a primary endpoint of weight loss at 12 weeks. Secondary outcomes included blood test analyses including diabetes markers, cholesterol, liver enzymes, inflammation, as well as a validated survey on sleep, and weight loss at 24 and 48 weeks.

The trial started recruitment in January of 2020, and the 12 week endpoint was completed in December of 2020. Of note, the trial was completed through the peak of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which was a feat in itself.

We’ll get into the results in a future post!

Citations

Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials – the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125(13):1716. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15199